THE SPIKE - BLAYDON HAUGHS - PART 4 of 5

THE SPIKE - BLAYDON HAUGHS - PART 4 of 5MEMORIES

BY EDITH ROBSON

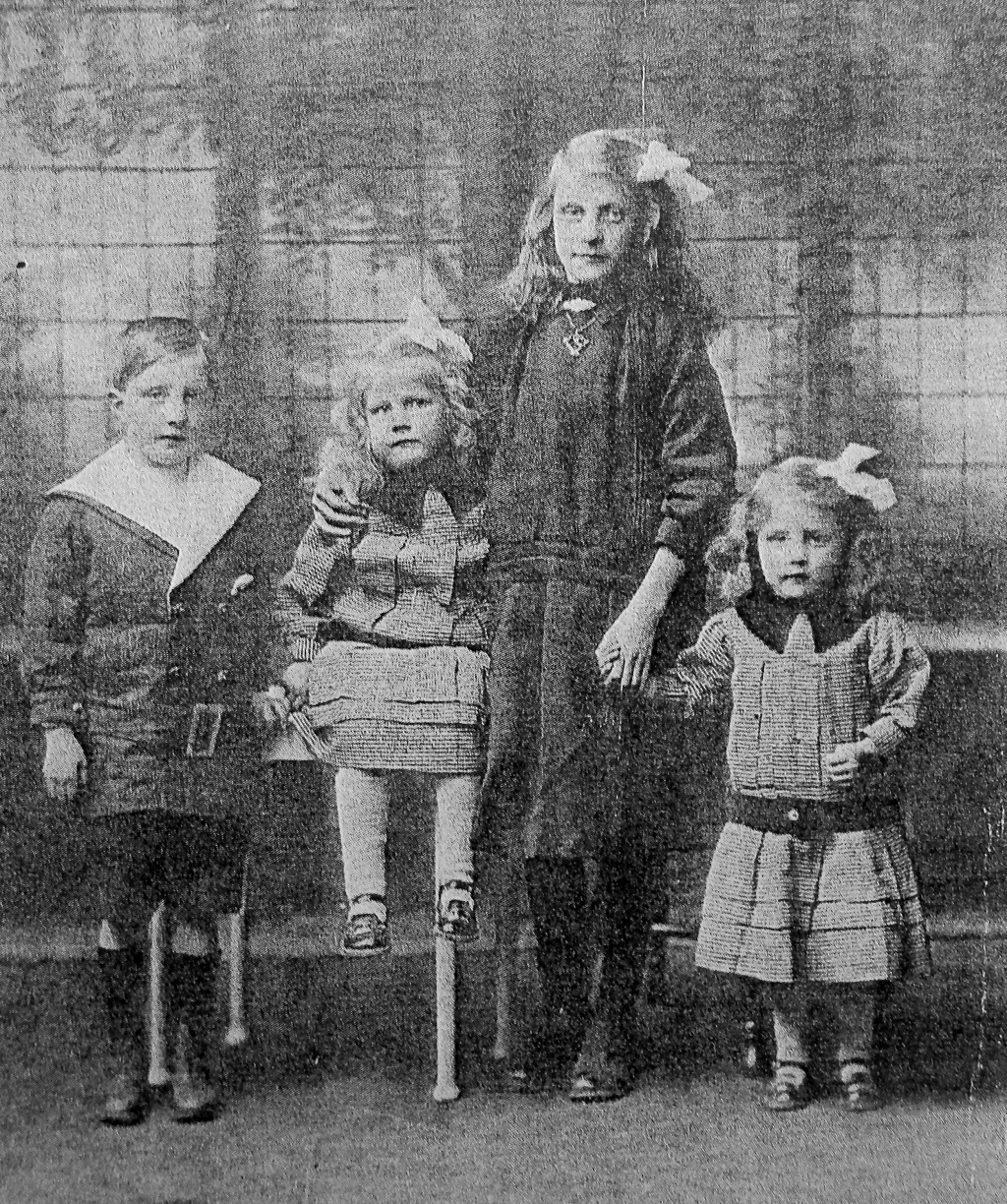

Photo right - studio photograph, Thirlwell Studios, Newcastle, January 1915

L to R, John Collingwood Liddle, Edith Liddle (the author, born 29th Oct 1909), Hannah Liddle, Mary Elizabeth Liddle

The text below is a verbatim transcription of a document very kindly sent to me by Gordon Robson, Edith's son, who resides in Australia.

I wish to express my sincere thanks to Gordon for permission to reproduce the document here on this website. The contents (ie. the text and family photos) are his copyright and must not be reproduced or copied in any way without his permission.

Gordon's introduction to the text is as follows - - -

The following is a collection of memories from my mother Edith Robson and originally they were hand written in a school exercise book from which I have copied them. The pictures are family photographs and local history publications which I have used to illustrate some of the subjects.

Edith Robson (nee Liddle) was born on the 29th October 1909 in Pioneer Street, Blaydon Haughs, Blaydon, County Durham, England. She was the second eldest daughter of John Pyle and Mary Elizabeth Liddle and passed away on the 8th September 2002 at Gosford, New South Wales, Australia aged 92 years having lived the later part of her life in Australia.

Signed Gordon Robson February 2007.

WASHING DAY

It's funny how a few spoken words can make your memory travel back in time. Daughter Sheila was saying how the washing machine saved her a lot of work and so I began thinking back in time. When I was about 10 years old my mother had an old fashioned wooden "Poss" tub, it was like a half barrel with iron hoops round it. It stood in the yard and was half filled with boiling water which she had boiled in a big iron pan on the kitchen fire, then ladled into buckets and carried outside to put in the tub. The dirty clothes were first sorted into piles, table linen and our best white "pinnys" (pinafores), then pillow cases and sheets, tea towels and towels and lastly the coloureds.

Everything was wet in buckets of warm water, soaped all over then put in a tub of warm water and “possed” with the posser. This was made of wood, a thick round stick about 3 inches across and about 3 feet long with a handle at one end. The other end was split into four so that when you pressed down the water swooshed around the stick and caused a turbulence cleaning the clothes. After that the clothes were rung out by hand and any dirty marks on collars and cuffs were scrubbed and then they were all “possed” again in clean water.

Coloureds were then finished off in more clean water, although in the mean time the pan with the water in it was back on the kitchen fire heating. The whites were soaped and put to boil on the fire then they were rinsed again and then put through “blued” water to make them white. All the clothes were then put through the “mangle” that is a machine that had two wooden rollers which were turned by a handle at the side. It was easiest if two people did this as one fed them in and the other turned the handle. The best things, table linen, shirts, summer dresses and pinafores and lace curtains were all starched, usually “Robin Starch”. The washing was then pegged on lines strung, with ours across the back lane, and as the stretches were very wide they needed clothes props to help to take the weight. These props were about 12 feet long and about 3 inches square and properly made lasted for years. As everyone usually had one you often borrowed your neighbour's when you needed it and no one ever said no as you helped each other, and even took each others washing off the line if you heard that rain was on the way and they were out of their home.

As each lot of clothes were dried they were sprinkled with lukewarm water and rolled up till ironing time, although sheets and towels were folded and put through the mangle to press then, properly done, they were beautiful and smooth. If it had been a poor drying day they were hung in folds on lines across the kitchen.

While the washing was drying Mam used to clean the kitchen up, scrubbing the kitchen chairs and “crackets” (stools) outside, rinsing them and leaving them outside to dry. In wet weather our tub was pulled right up to the back door and mother stood on the back step with an old coat over her shoulders. The yard was scrubbed and rinsed down (no hoses in those days) every drop of water had to be carried in a bucket. We were lucky as our landlord had put a tap in our big pantry off the kitchen. Usually the ironing was done the following day when the fire was “blazed” up so that the flat irons heating above the fire did not get smoked. You soon guaged the heat you needed for different things, cool for silk things, oh yes we did have silk blouses, hair ribbons, some of mine were 3 inches wide, and satin ribbons and sashes for summer dresses. Very hot irons were for use on shirts, table cloths and our summer dresses and especially our Sunday 'pinnys' which were made with frills all around the bottom and frills made the sleeves over the shoulders.

There was a feeling of satisfaction in seeing a line of washing that you do not get now with the cloths hoist. Then you achieved it. Now everything is thrown in higgledy piggledy into an electric machine, some Aura liquid poured in and press a button and leave it. The clothes are not really clean because there is no care taken with them.

Mam saved a lot of work later on when the landlord installed gas boilers in all his houses. It is a pity we did not have it earlier as Dad died suddenly and mother was left with 5 girls and a son to rear between the age of 1 year and 18 years to care for, so she started to take in washing to cloth and feed us.

My brother and I used to collect the baskets of washing, then they were washed, dried, ironed and aired ready for use and carried back all for 5 shillings a basket. Hard earned money, but mother had to be able to work at home as my sister Elsie was only 1 year old and my sister Mary was only 4 years old.

My eldest sister was also very sick for a while and was at home till she eventually found a job and her wages were a help. So that Mam could do the washing we all had jobs to do around the home although later we were granted Guardian Money, so much a week like a pension which came from a levy that was put on by the council to help the poor. It was not much but it was constant and with that, and what my mother earned, we could at least be kept fed. If the food was not exactly first class cuisine at least we never, or I can not remember, wanted a meal, sometimes only bread and beef dripping, but we never went hungry.

We always hung our washing out in the north of England even when it was snowing and when you brought it in it really had “got the wet out”.

Photo below - Elsie Liddle (left), sister of Edith Robson, with Joyce Lea her niece standing on the chair, at the rear of 11 Pioneer Street, Blaydon Haughs. Behind to the right is the "Poss pub" for washing, a wooden barrel with metal hoops.

DAD AT WORK

My father worked as a steel and metal dresser at Smith Pattersons on the Blaydon Haughs at Blaydon. They made “chairs”, the things which hold the rails on the sleepers on the railway, and pipes and ships boilers etc. The dressers using hammers and chisels to smooth all the rough places off the surfaces. Skilled work because too much pressure could gouge off too much and weaken the article and it was hot thirsty work as there were furnaces nearby.

Before he went to work at 6am Dad had a “pint pot” of tea and toast. The factory was just up at the end of the street so it only took a few minutes to get there. Just as well because even if the men were just 5 minutes late clocking on they were docked a quarter of an hour, even if they were working on "piece", that was when you were paid for the amount of work you did.

About 7.30am, Mam used to send one of the family with a large can of hot sweet tea and some sandwiches wrapped up in a white spotted red handkerchief (large like a neckerchief) to the factory. We first had to get permission from Mr Maddox the watchman who sat in a little hut near the offices at the gates, to go through into the factory, then we walked down a laneway till we got to Dad's workshop. When he saw us (he was expecting us) he would come over and take the can and sandwiches, then say “Want a bite hinny”. A lot of the men would take their breakfast with them when they went to work but Mam liked Dad to have his fresh. He came home for his midday meal as it was so close, only half an hour allowed but he said it tasted better away from the works.

My uncle Dick worked in the same “shop” and he would wave to us, in fact most of the men did, as everyone knew all of us young-uns. The shift finished at 5pm and it was a sight to see all the men streaming out through the factory gates. Those in the shops along the river bank took longest to walk out. Mam would sometimes send brother John with Dad's bait and I used to feel cheated as I would rather have that job than others lined up for us at home.

Father's father, Granddad Liddle, worked at the Glass Bottle Works, just up the road a bit, as a glass blower. We could go and watch from a very safe distance. It was hot as they had fires going to keep the molten glass “malleable” whilst they worked at it on the long rods. Each fire seemed to have its own gang working from it and each gang had it's own “gaffer” who seemed to finish off whatever they were making. They made bottles of every shape and size and I have seen some made for the chemists which stood 3 feet high, some with glass marbles in them which came up to the bottle neck when you tipped the bottle up to drink. Glass dishes, every kind of drinking glass, even to rolling pins, glass walking sticks which were hollow and then filled with coloured 'hundreds and thousands' and hung on the room walls as decorations.

They started making moulded glass by blowing molten glass into moulds where it set but you could always tell the moulded glass by the rim the article had when the mould was split away. The mould was made in 2 halves and clipped together. We had a glass pipe that Granddad made but it got broken and I did not realize enough to keep it. These things are very scarce now and being very fragile they were easy broken. You see men working with glass at exhibitions now but they use blow torches instead of furnaces and glass tubes which they weld together. These men who worked in the factories were experts at handling the molten glass but they served a long apprenticeship, I believe 7 years was the regular time and then had to pass a stiff exam to get the coveted name of 'Glass-Blower'. Granddad used to drink a lot of barley water which Granny made for him as it was, so he said, the best cooling drink he knew. He drank gallons of it and they needed it in that place.

As children if we heard it said so and so was “going to the devil” we used to think of Granddad's factory, but it could not be, because Granddad worked there and he had certainly not gone to the devil. Far from it. When the factories finished for the day we liked to meet Dad and Granddad at the end of the street and go home with them. They lived next door to each other, Granddad at number 9 and our family at number 11.

POLLUTION

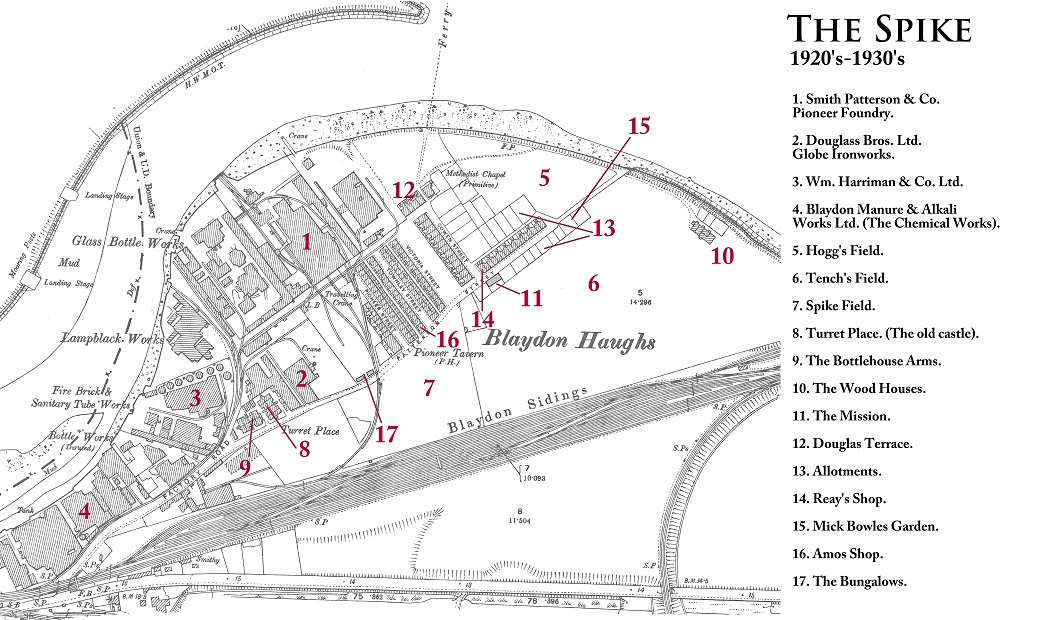

This pollution business gets me mad. We used to say “Where there is muck there is money” meaning you can not have everything spotless if you have got industry, and without industry you have poverty. I was born 500 yards from factories. They were in the shape of a half circle, not a very tight one but that shape and the houses radiated from the factories with the road (dirt at that) in between. The other end of the street had some waste ground and then the main London and North Eastern Railway.

The streets were cobbled, with stone built houses, not modern looking but comfortable enough inside, real working class houses. Along the road in between the factories and the houses we had a single line railway which ran along to the main railway line where it crossed the main turnpike road (the main access to the Blaydon Haughs).

Our house had downstairs an oblong kitchen with a walk in pantry at one end, a big square front room with room enough under the stairs for a bed, then upstairs, a big square bedroom and a long oblong room. Wooden floors, and a nice fireplace in one room upstairs, as did the front room downstairs, a fireplace with a fancy surround and hobs at each side where you could leave a kettle to heat slowly. The kitchen fireplace had an oven at one side and the other side had a boiler where you could heat water to wash up and get bathed with. We also had a concrete yard and a flush toilet enclosed in a 10 foot high wall. Most of the houses were sewered, in fact most had been done around the 1920's.

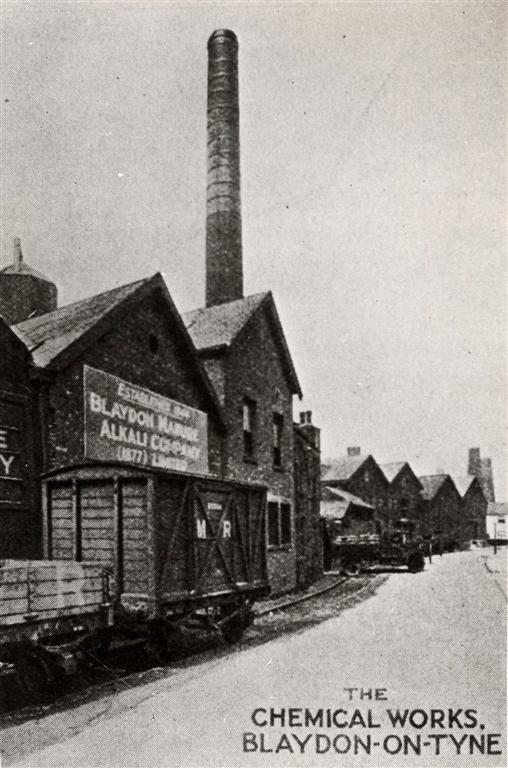

On the other side of the wall we had a light railway line taking the goods from Smith Pattersons factory to the main railway line. As well as Smith-Pattersons and the Bottle Works, we had Douglas Bros. where they made clay pipes, and Harrimans, where all manner of ceramics were made like toilet pans etc. The Blacking Factory were makers of boot polishes and black lead. The workers there were mainly women whose hands and skin seemed to be always ingrained black (no gloves or barrier cream in those days). Then we had the Chemical Works. Their kilns were at the side of the railway line and on cold winter mornings we would run across the road and warm our hands on the brickwork.

Lower down on the other side of the road we had an electric substation and next to it the Forge Works where, if you had time, you could watch the big hammer going up and coming down on the red hot steel sending up a shower of sparks like fireworks, then at the side of the LNER line at the corner of the village we had the railway sidings. Altogether a fine collection of pollution producing factories with smoke and dust belching out but believe me we had some very long living personalities.

My father was 44 years old when he died but he had pneumonia. I never knew him to be sick so it was a shock as most of the folks lived to a ripe old age and they had a saying “you'd have to shoot them to get rid of them”.

They all worked hard, had good plain food although most of the men liked a glass of beer at the weekend, some of the women too but they did not mix in the tavern. Men were men and did not expect women to be around when they got together. We had our fair share of drunks but drunkards as they are now, no no. A man had to show that he could walk home. We had a pub at the corner of our street, the Pioneer Tavern, a landmark you could see at some distance as it was built of white (porcelain) bricks which shone in the sun and were easy to see on a night time.

If a man was seen to be getting a bit “too much on board”, he was quietly taken to the door and advised to go home and sleep it off.

Pollution, I guess, is when some folks cannot be bothered to put up with it or the hazards, but it is still the same and even science has not come up with dustless industry and without industry, shops and offices would be non-existent. Someone has to have the muck (dirt) to get the gold to spend. Either that or you have the houses miles away and travel and grumble at the travelling. Even that causes pollution because of vehicles used. Maybe we lived too close to it to get any of it.

Note - Edith lived to be 92 years old and died of old age.

Photo below - The Manure and Alkali Works (known locally as 'The Chemical Works'. It was situated on Factory Road, Blaydon Haughs but well to the west of the rows of houses. Animal manure was processed to produce fertilisers.

TEENAGE YEARS

As teenagers in 1925 we were not just allowed to go out when and where we liked. I was 18 years old when I first went “sleeping in” as a maid servant, before that I was at home under Mam's watchful eye. Previously I left work for 7.30am and got home around 6pm. I had had a tea before I left the Roberts house but Mam always had a dinner ready for the family about 6pm, and by the time we were finished, cleared away and washed up, it was 7pm. By the time you put out next day's clothes, helped with the ironing (usually your own) and the young ones did their homework, the night was far through. The young ones were in bed by 8.30pm in the summer and 7.30pm in the winter but could read in bed for about half an hour, by then the call would come up the stairs “time you had that light out”.

In the summer you could sit outside and chat with your friends or read but in winter, well, it was nice to be in a cosy kitchen. I worked half day on Saturday but my sister, who worked at Armstrong's barber shop, worked all day till 9pm (12 hour shift).

Our picture houses (cinemas) were two houses each night, Monday till Saturday, first house 6pm to 8.45pm and 9pm to 11pm, and as Mam insisted we being in bed by 10pm we had to make it to the first house. We girls were only allowed to go if our brothers went and kept an eye on us. Our group seemed to be all brothers and sisters so it was really no hardship, apart from the boys expected us to walk in front of them till we got there and then escorted us to some seats and then they sat at the back. It worked OK because if any of us were bothered, as some lads used to try, we just had to say “our brothers are up there”. Coming out, they would wait and we all walked home together in one group, they had done what they had been asked - to “keep an eye on us”. Funny but a fair few married a partner from the group.

Sometimes in the summer on Sundays we would go down to Hogg's or Tench's (fields) on the riverside and have impromptu picnics, the lads would play cricket while we sat and watched, often parents would join in.

Funny but in all the years we travelled Factory Road to Blaydon, and it was a very lonely road being only lit by gas lamps which lit up just underneath the lamp, I can only remember one case of molestation. Maybe because there seemed to be more respect for women in those days.

I was a scaredy-cat in the dark and often I would be walking along and keep looking over my shoulder and hearing a trot-trot behind me only to hear “it's alright missy I'll walk with you if that's alright” then when we got to the end of my street they would say “I will wait till you get to your house then give me a wave when you get there” and looking back I would see the figure moving off. I wonder why we did not have any fear then.

Come the winter we would spend Sunday nights at each others houses. Each mother in turn would provide scones etc. for supper.

The lads got more freedom than the girls did, Saturday nights they sometimes went to Newcastle but always 3 or more together. The younger ones in our family got a lot more freedom than my eldest sister and myself, they were allowed to ride a bike and play tennis and dance. I always had two left feet and yet my mother and father were excellent old time ballroom dancing competitors. Mam used to say that in a waltz that your heel never had to touch the ground or you were disqualified.

After I went to a 'sleep-in' job I still had to be in by 10pm so it was no different, as when I had to return to work I sometimes had three quarters to 1 hour travel and had to get the bus by about 9pm. You did not have much of a chance of a boyfriend as most boys did not like to cut the evening short.

Being so close to the river, although it was big and deep enough for cargo boats to come into the factory wharfs to pick up iron ore or bricks, the local boys learned to swim. The girls did not swim in the river but later on they used to go to the indoor swimming baths.

Our activities might not seem exciting to present day youths but we did not expect that kind of life so we were content with our quiet ways. We did not expect our parents to keep us nor keep on giving us handouts. We stood on our own two feet, in fact we took a pride in getting a job and helping out at home. Perhaps parents now shunt off their responsibilities of their families by giving them too much freedom too soon at a later price. They do not want to be tied down is what it amounts to, I believe.

Photo below - Temporary housing on The Spike, circa 1920. After the Great War there was a shortage of housing. Two old railway carriages were brought to the designated site by the Spike steam engine shunter 'Pioneer', then converted to 'bungalows' and are shown on the map above.

EARLIEST RECOLLECTIONS

My earliest recollection is of going for walks with my eldest sister on Sunday mornings after chapel. The Methodist Chapel was only five minutes walk from our home and by the time I was five years old Hannah used to take sister Gladys and I. My brother John was there as well.

We went on Sunday mornings for the 10.30am service, the little ones went into the Sunday School in the schoolroom at the side of the chapel, while the big ones went to the adult service in the chapel. After we came out about 11.30am Hannah would take us out for a walk along the river bank as far as the waterman's cottages (we always called them the 'wood houses') then up past Hogg's Field, up past Patterson's buildings then home where mother would be waiting with dinner ready.

Chapel was a good deal in our lives, we liked going and the folks were friendly, our Sunday School teachers were very patient and as we got older we joined in, most going to the chapel. Mam went with us on a Sunday night and we all had to sit very quiet at the 6.30 Sunday evening service. Once a year we had an anniversary service when we all said recitations or, if you had a good singing voice, well you sang. I had a good memory so was often given a long piece to say. I was always worried till after it was over in case I made a mistake as Mam was very strict. I was alright once I got up and started. We also used to sing a cantata at evening service, but it was a good job that I was never asked to sing solo. There were some really good singers in our choir.

We were not a rich congregation but anyone who needed help never went without. There was a harvest festival when everyone brought something on the Saturday afternoon and the chapel was decorated with the fruits and vegetables from the gardens and the fields, then on the Sunday morning we held a special service.

“We plough the fields and scatter, the good seed on the land”, how we sang that hymm and how we mean't it. On the Monday night the produce was auctioned and the taking were donated to the overseas missions. Prices were very reasonable, the only thing that brought much money was the bread shaped like a sheaf of corn usually donated by Hogg's or Amos shops.

Once a year in the summer we had a picnic on a Sunday when we usually gathered at Hogg's Field at the back of the chapel and walked along the toll path by the river to Scotswood bridge, around the bridge buttresses and continued along the turnpike road to Swalwell bridge, then along the footpath to the picnic ground at the side of the Derwent river. As we went past the Old Mill the daring ones would sneak out of the “Crocodile” and run to have a look at the mill race.

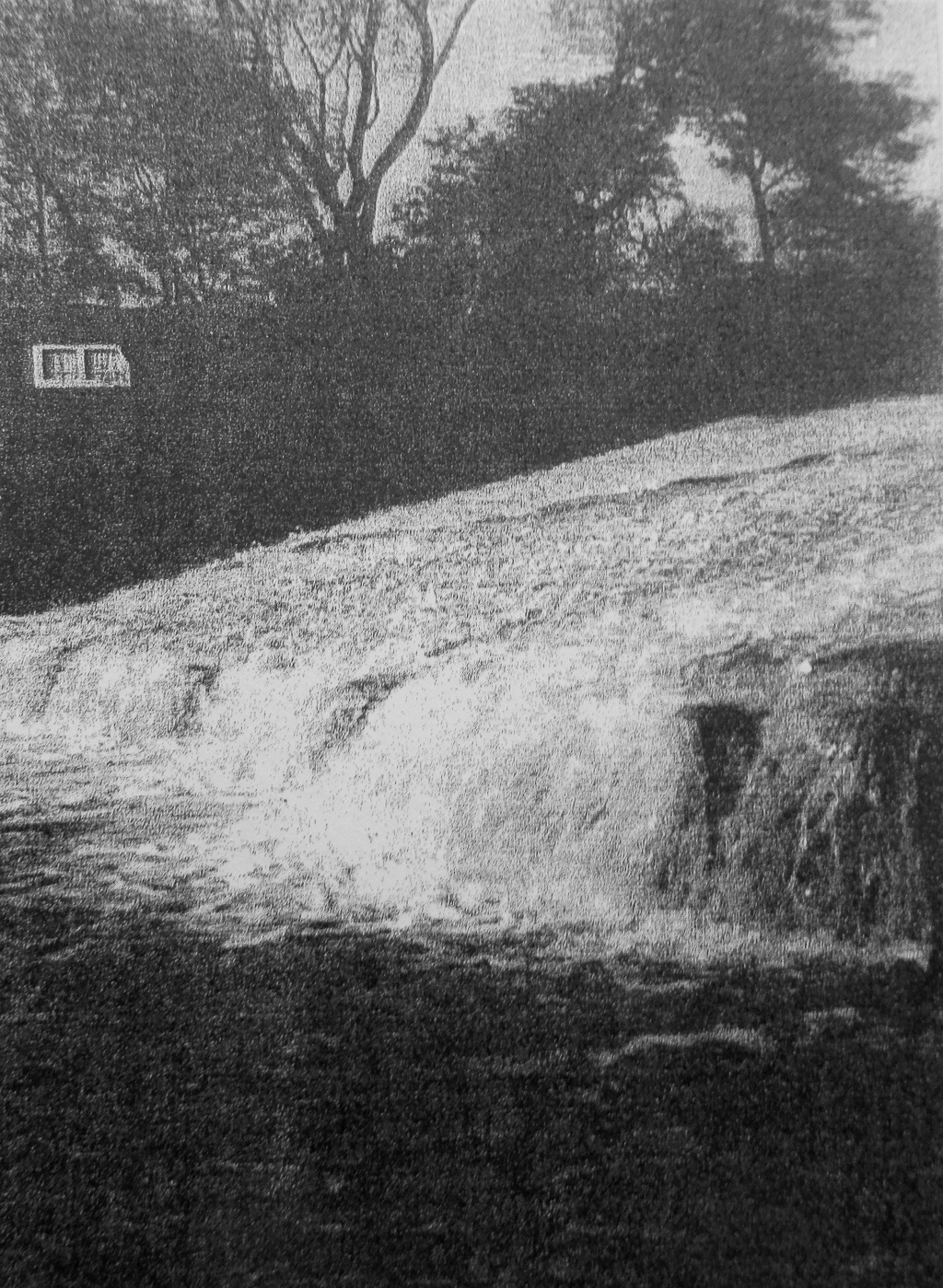

The parents were always glad to sit down when we arrived but of course we had to explore even if we had seen it all the year before. It was always different and we could paddle in the river or the very daring ones would walk up the Ladies Steps. These steps were the width of the river and formed a sort of weir, cascading water formed a miniature waterfall. At the side nearest us there was a break where the falls were not so heavy and if you did not mind a little splashing you could walk up the steps. Of course we were always warned not to go all the way but trust some bright spark to go further.

At tea time we were all lined up and were given a bag of cakes and as we had been told to bring a mug for tea and had as much sugar as you like as long as mother was not watching, and we really enjoyed the meal. The teachers organised games and races for the children and even some for the parents. By 5pm came we were all (well most of us anyway) ready for home. The road home seemed much longer than going but by that time some of the dads were on the road to meet us and took turns carrying the little ones. Some of the wise mothers had taken strollers which often carried a double load and some of the bigger boys 'piggy backed' the littler ones as well.

Chapel was a place where no matter how poorly dressed you were you were welcome. I went twice every Sunday till I started work and during that time I made many great friends. We only had a lay preacher on normal Sundays but once a month the minister from Blaydon Chapel came and took the evening service.

Two photos below - "Ladies Steps" on the River Derwent at Swalwell. A dam constructed to raise the water level on the river so as to feed into the 'Mill Race' which was used to power the Steel Mills and later the Flour Mill on Mill Lane. Constructed of sandstone blocks in courses, like steps, it allowed the river water to cascade down, and the water from the mill race rejoined the river after it had passed the Keelmans Bridge.

Two photos below - Left - St. Cuthbert's Place, Blaydon, taken circa 1890. It was to number 7, the first door from the right next to the large rear entrance, that Edith Robson moved with her husband Albert, after they were married, to live with his family.

Right - St. Cuthbert's Church School in St. Cuthbert's Place, Blaydon, also taken circa 1890. The school, on the left of the picture, was attended by Albert Robson, until the new Blaydon Board School was built in 1898.

WASHING CHANGES

When I was first married I was using the old fashioned "Poss Tub" and the big iron pan on the fire till one day when I was lifting the pan back into the fire the wind blew my apron towards the flames and just in time I drew back to safety, then after a talk with my husband, who was not really keen on the idea, I bought a pair of trousers. Talk about "talk". Just fancy "trousers". That's just not done. A while later the neighbours had even more to talk about, I bought a "Dolly tub", a galvanised corrugated tub instead of the heavy "poss tub". Not long after one of the younger neighbours started wearing trousers and another bought a dolly tub for use on washing days. The old ladies decided that they would stay as they were and stick to what they had but gradually came around the idea that "Trousers" were alright but only on washing days.

I could not afford a washing machine but after a while was able to save up enough money to replace the iron pan with a gas boiler, another nine day wonder said the old ladies, but they were not shy about coming and asking to borrow it. My husbands' mother lived with us and she thought it was all a waste of money.

When we moved to Old Toll House, we managed to buy a washing machine, a square box with a handle on the lid. This handle you pushed backward and forwards and the paddle inside the washer swished the clothes. It was real hard work, and I really do not think it was much improvement on the tub. When we finally got an electric washer we thought we were "it".

The first washer I used was when I worked for the Hurst family at Fern Avenue in Jesmond in Newcastle. It was like a flat bottomed barrel on it's side and when you lifted the lid there was a wooden cage affair inside. You opened that, put in the washing, added some grated soap (no soap powder in those days), put in the hot water, fastened it up again and turned a handle at the side which rotated the cage and swished the clothes. When you had done them long enough you opened it up and fed them through the rollers. No wonder we developed muscles or that we did not need sleeping tablets on a night time, "we worked".

I once saw the "original" mangle, or one like it, two round flat stones about 2 feet across and really smooth. Two people lifted the top one off, the clothes were then folded to fit on the bottom one, then the top one was put back into place on top, then after a few minutes a second stone was added and "hey presto" the water was squeezed out. At least it did not need electricity. Could use that idea if you were camping but where they get these stones I will never know.

I have seen my Mam roll a dress or blouse inside a towel to take the water out when she did not want to wet the mangle. Easy enough then to dry the towel alongside the dress.

The box iron was another new thing to me at the Hurst household. A hollow iron held a piece of iron the same shape that fir in the hollow, rather like an oval pointed at both ends. You made the inner piece red hot in the fire and dropped it by means of a hook which fitted in a hole in the middle into the iron and then put on the lid to which was attached a wooden handle. Of course you had to be very careful handling the red hot piece. The red hot piece heated up the iron for you to use when ironing. Mam had a shield which fitted over her flat iron so that the iron did not mark the clothes. At school at Domestic Science we were taught to rub the iron over bathbright on a paper on the floor to smooth it and to make sure it was clean and did not mark the clothes.

Acknowledgement - thanks to Newcastle City Archive for this photo on the left below. It further illustrates the rigours of life and wash day, with a row of "Poss" tubs, hand mangles and washing line complete with washing line "clothes props" (right side foreground). The photo was taken at Lemington Glassworks by AD Walton. The brick building on the right is part of the works. The 'Poss' tub and mangle were taken at the 'Beamish Living Museum of the North' by Stephen Veitch in January 2014.

THE METHODIST CHAPEL CONCERT

“Welcome to our princess Ju Ju,

Years bring her joy,

without alloy skies always fair and blue, blue,

Hail high and might hokey Pokey Tippee top top”

(Oh Verity Moore)

That tune takes me back more than half a century. Is it so long? So plain in my memory that a tune can bring it back.

In a not so very small village in the North East of England at Blaydon Haughs our Primitive Methodist Chapel decided to produce the same play as Verity's school. I think the year was 1920 or thereabout.

In the parts our Potentate of High Estate was Dorothy Chapman "renowned far and wide", plump and jolly, an ideal potentate. Princess Ju Ju was Gladys Parkes, a slim blonde and our Prince Charming was dark haired, light skinned Lizzie (Elizabeth) Armstrong. I am almost sure I have the names right but no matter, they were just right for the parts. Our villain was hissed and booed to his downfall. I think he was one of the Walley Boys.

The fun we had concocting costumes, kimonos for the chorus with crepe paper and chrysanthemums behind each ear, even some of the sashes were paper. Fans of all descriptions fluttered madly at every opportunity.

Prince Charming in tights and oh boy was she (he) handsome, no wonder Ju Ju fell for him. Me, I was the King's Messenger, very self conscious in a gold satin cloak of coloured brocade, kindly loaned to me by one of our oldest parishioners who had worn it in days gone by, for visits to the opera. I felt much more at ease as I imagined that it disguised my really plump lines. How many times I went down on my knee to our “High and Mighty” I shudder to recall. I suppose I got the part because I had a good memory and did not need any prompting as to stage entries. It was winter time but no-one missed any practise time, come hail or snow they all made it. I wonder what parents thought about our eagerness we displayed to be off on those nights.

Our scene shifters were many, but chief among them was a coal black West African with gleaming white teeth who we knew as Mr Lee. His family were born in England and were marvellous painters and the scenery they painted created a sensation. Nothing was too much trouble for Mr Lee and his boys, Mrs Lee was white, much to our surprise but the whole family dug in a helped. Best mannered family I have ever met.

I wonder whatever happened to all our Chinese fans? Some lent, some bought, and others made at home by some really clever women, but they were all marvellous. It was really good fun while it lasted and as true love prevailed and the final curtain came down the audience applauded us and we applauded our Sunday School Superintendent, who had done so much and worked so hard to bring us together as a team.

It was not the first show we had put on nor was it to be the last but for some reason it was long remembered, perhaps because it has the fairy tale ending of "happy ever after". There was a happy ending to one couple and that was when in later years Dorothy Chapman eventually married Archie, one of the Lee sons and they were very happy.

ODD CUSTOMS

Years ago in England (or should I say from 1910 onwards) we had some odd customs or at least to the present generation, may be they would have a name for them I suppose. To start off with, when a baby is born each person who visits the baby is supposed to give it a piece of silver (usually money) then it was a sixpence or a shilling, and the grandfather, if he had a good job, would give it a piece of gold, maybe a sovereign or a half sovereign, more especially if it was a boy. The first 3 houses that the baby was carried into had to give the baby it's "almo". A little parcel containing a candle and matches to light it's way, a three pence or sixpence silver piece for it's wealth, some salt without which you cannot survive, and an egg as the seed from which the baby came.

My mother told me this, but different counties have different customs. I know that she always gave them, and so did I when I had a house of my own.

The child was registered with the authorities as parents had to do, then most people like to have their child christened in a church or chapel. After a name was chosen you had to have godparents, usually friends or relatives, and if it was a girl you needed two godfathers and a godmother, and if it was a boy the reverse, but in some cases parents could be godparents.

After arranging with the minister when and where the christening could be held, the next thing was the "dress". A lot of families kept a christening gown which was handed down from one generation to the next, and some of them were beautiful and they were treasured. In my time a baby wore to church a singlet, then a napkin, and next a barracoat, a garment made like a rap around sleeveless coat, with only straps at the shoulders. This was wrapped around and the bottom part folded up like a bag and pinned. Then a petticoat, long and frilled at the hem and fastened at the back, followed by the gown itself usually tucked and frilled with tiny puff sleeves which were lace edged.

My aunt's christening gown was cream silk with a carrying coat over it of cream serge (a woollen like material) which had a big cape collar which reached to the elbows, both coat and cape being trimmed with rows of cream silk braid. The hat was rucked and gathered almost as big as a woman's toque. This was tied on with wide ribbon strings, left for a girl, and right for a boy, in big bows. The final touch was a net veil pinned to the hat at the back, which covered the face. Although this was taken off with the hat when the baby was handed to the minister, but when the hat was replaced the veil was left hanging down the back except in cold weather when it was used to keep the cold off the baby's face.

The baby was carried to the church by the parents but carried by one of the godparents on the way home. As a rule only close relatives were invited home for a cup of tea and grandparents if they lived close by. Only "well to do" people made a bean feast for the christening, but some parents did not bother about taking the child to be christened (or baptised I believe is the correct expression).

When our family emigrated to Australia on the S.S. Otranto, the captain held 2 mass baptisms when whole families were christened and the ships bell was used as the font.

Oh I forgot, when the child was carried from the house the woman carrying it was given a small parcel which was given to the first person of the opposite sex to the baby. The babys "piece" contained a piece of cake, scone, sandwich and a small silver coin for luck. Many a bewildered recipient, puzzled at being given it, had to seek an explanation elsewhere to why they had been given it. Godparents often bought a silver engraved mug or broach as a token for the child. Poor baby, layers and layers of clothing.

Among the very wealthy the godparents made a gift of money to the midwife who helped when the baby was born, but not in our class as they could not afford it. Our midwife did not expect it as she was paid as a nurse, but most times she was regarded more as a friend.

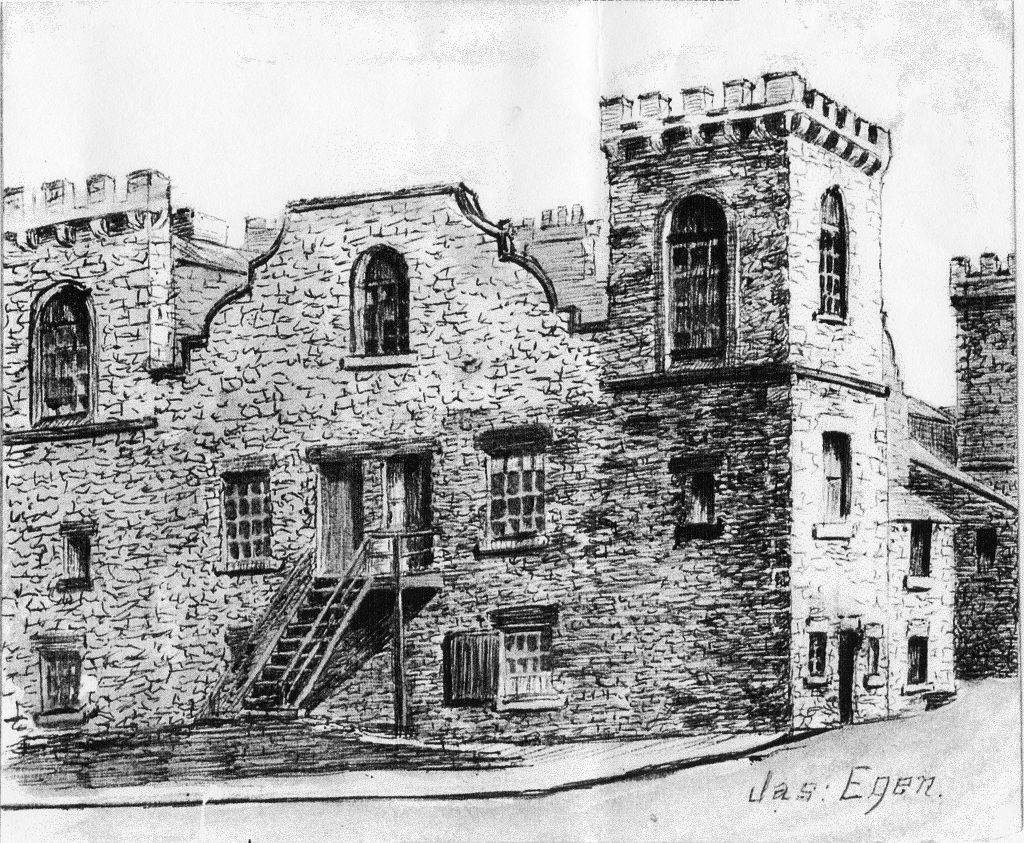

Photo below - Hand sketch by Jas Egan in 1964 of Turret Place, on Factory Road, Blaydon Haughs which was renovated and adapted for use as residences for the local factory workers. It was originally a family home of the Selbys, a wealthy land owning family, which had been deserted and had become dilapidated. This is only one quarter of the complex which was joined by cart yards and surrounded by a dry moat. It was demolished in the mid 1930s.

WEDDINGS

The first wedding I can remember much about was that of my eldest sister Hannah. Her husband to be was a Londoner, a real cockney, 6 foot tall and broad shouldered, but while they were courting she had to work Friday and Saturday nights as a man's hairdresser till 9pm. So Sid would take my sisters Mary and Gladys, and brother John if he wanted to go, and myself to the Empire Cinema, so it was no wonder we thought a lot of him.

When we came out about 9pm we would wait for Hannah coming from work and they would walk us home before getting any time to themselves. As Sid's family came from London and his parents had died when he was a young man, there were not many of his family to invite to the wedding. Not many working class families could afford bridesmaids and veils in those days, most opted for something serviceable. My sister wore a light navy two piece costume skirt and jacket with a hand crochet silk jumper in a very pretty gold colour. Her bridesmaids wore a brown two piece with cream blouse. My sister's hat was a jet "halo" and my mother had a lavender crochet silk jumper with her navy suit and a navy hat with ostrich feathers, only a few weeks later they exchanged hats as they suited each other best.

As mother thought at 15 years I was old enough to get dressed up, in a dress and a short jacket in very dark brown with a brown beret type hat. So all dressed up for the first time in my life I rode in a hired car to the church with Mam. My younger sisters were left at home as they thought they were too young to go. As the car left the house with the bride it was custom to throw out some handfuls of small coins and as this was well known, even grown ups stood and shouted "Hoy a penny out".

After the service and the bridal couple left the church, they also had to "Hoy oot". In some of the country areas some of the churches had lych gates through which the couple had to pass and the groom had to pay a few men who barred their way before being allowed to pass.

When we returned to the house a tea was already made, as some friends had prepared it all and had set it out in our big front room on the dining table. It looked good, with Mam's best white damask tablecloths and white fluted tea set, which was of fine bone china and a gift from my father when they were married all those years ago. Hannah had a white set with a thin green line around the top that someone had given her and between the two sets and all the glass dishes, the table looked good. After the mea things got very dull for we young ones so Mam's youngest sister, Aunty Florence, took myself and one or two of the others by bus into Newcastle to the carnival at Marlborough Crescent. I was at several weddings after that but one that I remember was that of a friend of my husband and I, who was married in Newcastle at Westgate Hill. There were 200 guests at the hall, and the bride made her own white satin dress with tiny buttons down the back and a huge floaty veil and train. She also made the 2 bridesmaid's dresses in apple green, daringly backless, with scarves which draped from the front and hung down the back, a little flower girl in "Kate Greenaway" style in white satin, and a Lord Fauntleroy white satin page boy.

These two little folks had a great time as they discovered they could slide on the polished floor and slide they did, till his pants and her pantaloons were a different colour to their outfits on their behinds. When the couple left about 10pm for a mystery destination, a lot of us went to her parents' house to continue the celebrations. Her parents owned a general store.

Things got very late, too late for a lot of the guests to catch buses home, so everyone just slept in chairs, on tables, in fact any port in a storm. I was expecting our first child so I was looked after and a bed settee was unfolded in a room downstairs and I went to bed still dressed, leaving my husband yarning in the kitchen. I woke next morning to find husband fully dressed next to me but to my surprise, I found someone else on his other side fast asleep. A petty officer from down south missed his train and had made his way back to the house, found all spots taken so husband said "Just kip on the other side, it will be alright mate". After getting washed and tidied up we were told to help yourselves to breakfast, and as I mentioned they had a store and ham and eggs and tomatoes were plentiful. They asked us to stay for the weekend but I said we needed changes of clothing, so declined.

One of the simplest weddings was that of May Atkinson at the Blaydon Burn in 1933-34. The couple wanted it very quiet so settled on a time at the church for 9am. Lichfield Chapel was about 20 minutes walk from their home and all invited walked with the exception of the bride and bridesmaid. I called first at the house as we were "special friends", then Sally Oliver and I walked up to the church (all up hill - I might add). There were not many people in the church but I can still picture it, the bride was in a sky blue dress and hat and her maid was in red. The men wore navy suits and as they knelt at the alter the sun came through the stained windows at the side and they were bathed in the most wonderful rainbow colours. Even the ministers white surplice took on the colours then I heard someone beside me say very softly “Happy the bride the sun shines on today”.

The bridal couple had the car to ride back to the house and then the rest had to walk, although this time it was downhill and by the time we arrived the wedding breakfast was waiting. The mine where a lot of the man's friends worked was close by and a lot of them called in as they came from work, my husband included. No false pride there, it was just "'Wash your hands man and sit down and have a bite". As several wives were already there, well they just sat down and had a bite.

We went to the wedding at the Hobsons (near Lanchester) of my husbands cousin Katie Neesham and we had to travel by bus (no one owned a car in those days). Alan, our first son, looked really nice, at 2 years he had beautiful blonde hair and clear fair skin. I had dressed him in black velvet trousers with star pearl buttons up the side, white satin shirt and black patent leather shoes and white socks. Going towards the corner where we turned, he let go of my hand and fell. Of course he chose the only puddle in sight in which to fall. Grabbing him up my white gloves were covered with mud but we did not have time to go back so just had to clean him up the best we could.

We made the church on time although we had to use two buses, then had to walk to the bride's house for tea. Talk about a crush, so many people had been invited the house was crowded, folk were sitting in the bedrooms, on the stairs in the lobby and overflowing to the back yard. We of course were in the yard. The feed was set in the large kitchen, very few old time houses had lounges, in fact any extra room was called a front room or parlour, so the kitchen was full.

The bridal couple, attendants, grandparents, parents, with some aunts and uncles, all sat down first but as customary in small mining villages, the minister was invited. Fair enough but when we got up to toast the couple, he talked and talked and talked. I believe he was finally shut up by one of the women "waiting on" by clearing away his cup and saucer. It was very cold outside and we did not have any seats, although the men squatted we women folks could not and the bairns wanted to run outside the yard. I think I remember we were the fifth "sitting", mind you none of the others took a quarter of the time as the first one so it was get in, get out and away home.

Family weddings you took in your stride, everyone knew each other so you enjoyed yourself but I never liked those affairs where you never knew whether to dress in your best or for comfort.

When my youngest sister was married it was wartime and they were both in the forces and his family lived in Yorkshire, so we took it on ourselves to fix it up among ourselves, of course no-one expected luxury in those times.

As food was rationed we pooled our resources and Gladys (sister) had two friends who made and decorated a beautiful three tier wedding cake, but you can imagine a three tier wedding cake being carried on a bus. Well it was and emerged immaculate, not a piece was damaged. Food enough to feed guests was the next problem solved. I was working at the time at a home bakery and like all bakeries they were rationed in the amount of food they could bake. The owner Mrs McLaren let me have some big meat pies, cakes and jam tarts, then the Blaydon Co-operative Society allowed catering for 25 people (the limit they had). Next a friend said that there was a place at Scotswood where they could supply some more, so off we went and sure enough we came home with slabs of cake and some tins of meat.

Then we realised Mam's house was nowhere near adequate for even the few we would have and as there were no small halls available, in fact letting of halls during the war was frowned upon, then out of the blue sky came help. While talking to one of the lay preachers from the chapel about Elsie's wedding he said "Why not ask the committee to use the Chapel". Well, we asked and they agreed and where we thought it would be the school room at the back they said we could use the Chapel and use the school room for the get together after the meal. One condition, no wine to be drunk, even as a toast, of course that was no hardship.

The seats were all pushed back to the walls and the tables in front of the pulpit and we had ample room and needless to say the preacher was a welcome guest. We solved the problem of the toasts by using soft drinks and when the guests were ready to go home, were invited to call round at Mother's house where they could toast the couple in wine or spirits as they wished.

It was winter, March in England, and Elsie and Frank had a few days leave so we fixed them up with a cottage at Ovingham and when they were ready to leave several of us escorted them to the railway station at Blaydon about 20 minutes away. At the station Frank, who was in uniform, realised that he had forgotten his overcoat, so dashed back to the Spike to get it. Imagine the dismay when the porter came along with his flag to start the train but after we had explained the trouble he said "Well we will give him five minutes" and went along to the driver who waved to us. Frank came flying into the station and we almost threw him into the carriage. To the cheers from us and quite a few strangers also, who had realised what was happening, the train pulled away from the station. I wonder if Elsie ever realised how many people helped that day.

Oh yes, her Tudor style bridal outfit was bought second hand from a bridal shop, coupons being in short supply as we wanted to buy them bed linen with what coupons we could put together. Then we all walked back to the chapel where we found that the folks had moved in and cleaned it all up and put it ready for service the next day. What can you say, just thank you. So it was back to Mam's and then a long walk back to High Blaydon and home. Weddings in wartime were not an easy thing.

Here in Australia one wedding that does stand out was that of my brother's eldest daughter Carol. The day was set, everything arranged, and it began to rain and it rained all the week, talk about water. By the time the wedding day dawned we were squelching, so off to the shops went my sister in law Carrie and bought yards and yards of clear plastic and out came the sewing machine and she made huge overskirts for the ladies, the out came the beach umbrellas from the house to cover the people from the house to the cars then in and out the church. We lived up a road were there were no buses so managed a lift with the farmer's wagon. Went to the hairdressers as arranged but might as well have saved time and money. When we arrived at the church, we found everyone else in raincoats and umbrellas. The hall at which was to be held the reception was dry to start with but by the time everyone arrived and added to the racks of wet coasts and boots it began to look like a refuge camp. My brother John, who had been running back and forth holding umbrellas over the women folks, was drenched. He first shed his shirt which was dried on the radiator then replaced and then he had his coat dried. The roads into Dapto were flooded so guests from outside could not get in and by the same token the honeymoon couple could not get out so end up spending the night in their own home. As we had arranged the catering ourselves, buying in what was needed for a hundred guests, we had oodles left over, but no waste as my sister in law just gave boxes of food to other guests as they left. The weatherman has a lot to answer for the success of the bride's day.

When my brother John was married we had to travel by bus, then tramcar, then walked to the church, but when we got there the church doors were closed. Thinking that we were at the wrong church, we enquired from a man on the steps and were told that the ceremony had started and that you could not get in and no amount of persuasion would make him open the doors so we had to wait. Have you ever stood outside a church in all your finery with passers by staring, I could have shaken him. It seems it was customary to close the doors as the minister objected to latecomers and of course the fellow outside was tipped by the bridal party to open the doors in the beginning. I wonder if he closed them for funerals as well.

Working class folks seldom sent out invitations to a wedding and it's been known for young fellows out for a bit of fun to join in the group of guests leaving the church and follow them to the reception and sit down for tea. So long as they did not come in contact with either bride or groom they were safe as each party imagined they belonged to the other side. I will warrant this happened as I know of it happening at least twice. Gatecrashers are not a new innovation.

Photo below - Wedding photograph of Frank Butcher and Elsie Liddle, youngest sister of Edith Robson.

SCARLET FEVER

On my 14th birthday I was taken off to Norman's Riding Isolation Hospital with Scarlet Fever. In those days all contagious diseases were isolated which probably accounts for the hospital being out in the countryside in a lonely spot at the back of Winlaton.

After I was taken away by ambulance my mother had to take all the food out of the pantry and cupboards and take them next door to her parents and the family was made to leave our house for 12 hours. The Health Authority sent two men to seal up all the doors and windows, open all the cupboards and drawers and fumigated the house with, I believe, sulphur fumes. At the end of 12 hours Mam had to go and open the doors to clear the air of fumes then she could go in to open the windows and return home.

I, in the meantime, was busy being bathed and dressed in hospital garments, examined by matron and the doctor and put to bed in a huge ward full of females, both women and children. I was lucky as my bed was quite near to a window and by turning over I could see the main gate to the hospital.

The length of time to be kept in the hospital was six weeks. Trust me, as I had severe throat trouble and ended up with a ten week stay. If you were well enough at the end of one week you were allowed out of bed to sit around the ward but not me, each day Matron would just shake her head sideways.

The ward was huge with a whopping great fireplace at one end and near the other end a big stove. Seats were built around this stove so that you could sit and talk or knit but as normal too many patients and not enough seats so most time the seats were occupied although it had one snag. The stove was a beaut but as all the windows were wide open you could take your choice, face the stove and freeze your back or vice-versa.

After a few days I had a visit from the boys ward as one of my school friends had been in for three weeks, seems like he had caught it from a cousin and had passed it to a classmate and it had gone the rounds of the class.

Our nurses were nearly all probationers with the exception of the staff nurse and sister in charge. The day started at 5am when the ward maids came on duty to clean the fireplace and stove then they put on a huge pan of oatmeal porridge. Next came the nurses and the water basins for you to have a wash although those who were able were allowed to go to the bathroom but timed very carefully so you missed the patients from the male ward. Back to bed to be served trays of breakfast, oatmeal porridge with plenty of milk and the nurses would ask "how many toast" and you would also be given slices of bread and butter on your tray with mugs of tea or cocoa if you preferred. That bread and butter was delicious, it was bread, not like the kind we get now. This was followed by getting cleaned up again ready for matron's visit, not a thing out of place, not a crease in the bedspread so how we hated these visits although for some the second round with the doctor meant moving to a side ward and almost ready for going home.

You were not allowed visitors from outside but twice a week parents could come and stand outside at the fence and you could stand on the inside about 12 feet apart and shout to each other. No presents were allowed but parents could bring fruit, eggs or chocolate with your name attached. This was all pooled and each morning a tray was brought around so everyone got something but eggs were marked for your own tea, lightly boiled and they tasted good. Food was plain but she must have been a good cook as it always looked and tasted so good.

The kitchens were right at the end of the land along with the staff quarters. I used to wonder how could the nurses and kitchen staff and laundry maids and gardeners and porters and ambulance men who all lived out, all got to go home while no visitors were allowed. When I asked one of the nurses one day she said "You will find out one day when you go home". I did. All staff stripped naked and went first into a room wearing a mask where there were sulphur fumes and then into a second room with showers. As the nurse told me that even the showers could not get rid of the smell of the sulphur and they liked to walk towards the main road to get rid of the smell.

At Norman's Riding there were different buildings for different diseases, Typhoid, Small Pox, Scarlet Fever, Diphtheria and others. Some of the buildings had only one or two patients in but all were kept separate but as you got well enough you could wander outside although only in certain areas. Of course, as it was winter you did not linger. You were not allowed to go home even if you felt well enough, until you had finished "peeling" when all the dead skin was gone.

I believe that in England there has been no need for isolation hospitals for years and Normans Riding is now a geriatric hospital.

Christmas came and most of those who had gone in with me had gone home. Then a few days before Christmas came, ladders were brought in and the nurses, bless them, gave up off duty time and we were transformed to "Fairyland". It was still our ward but oh it was wonderful, and between the greenery and streamers, we had a huge moon with an elf sitting on it, while silver stars were swinging, fairies who looked really real were flying and the Fairy Queen was sitting in a bower. The men's ward was a pirates den but we voted ours the best.

Then on Christmas Eve every bed had a stocking hung on it, then early, and I mean early, in the morning, even for our hospital the ward door quietly opened and three figures moved in (one in red, one in black and the other one at the back in blue). We had been told we must sleep because Father Christmas did not come till all good people were asleep. I was not, as I had a bout of throat trouble again and as usual I was propped up in bed with pillows. I dare not move and tried to hold my breath till they passed and then I opened my eyes. As the three figures went out of the ward Father Christmas stopped and looked back and I am sure he knew I was not asleep but as matron vanished around the corner to the men's ward he bent and kissed the figure in blue, and guess where there were? I dare not laugh as I knew the figure in black would be back if she heard me choke. Next morning when nurse asked me what Father Christmas had left me I told her that I had not been asleep but had kept quiet and quite still. She was not much older than I but she looked at me and said "Good Girl". I often wonder if that kiss led to a romance. She was our favourite nurse because she could always find time to hush the tiny ones to sleep.

I was lucky as my Sunday School teacher had left me a box of chocolates, a whole pound box, and I was allowed to keep them to myself for as matron said "It was Christmas". I did share some with my friends but a whole box for me. Any presents you had sent in would have to be left behind when you left, but I could not leave them behind when they were inside me could I?

Well, New Year came and fairyland vanished somewhere and our bare ward came back, old faces went and new faces appeared, mother still came outside the fence and matron's head kept shaking and I kept getting those sore throats. Salt water gargles one hour followed by potash gargle the next but always after my nice warm milk till I grew to hate those mugs. I was allowed up but home no, till one day the doctor said "Well maybe in a week if?". At the end of the week it was "We will try her in isolation and see", and I was shunted off to a very small room or it looked small compared with the ward, but still had room for four beds. Two days in that room and they said "Well if we can get an ambulance".

The snow was thick on the grounds and snow ploughs were keeping the roads clear and it was visiting day and mother came on her usual visit, said I “I can walk home I am sure”. Down came the brows and matron said “Too far, beside we must be sure you get home safe, hospital procedure”. Mother was told (over the fence) to come to the gates and after a conflab matron said “All right but you must ring me as soon as you get home”. Quick smart I got dressed in the clothes which I had been taken in 4 weeks before and very quickly walked outside, waved to the faces at what had been my window and joined Mam outside. Part way down the road I stopped and looked back, Mam did too, 10 weeks in there and for 10 weeks she had walked all the way just to stand in the freezing cold to be able to shout to me through the fence. Mam said “Whew you smell” and I must have because I had the same as the staff, sulphur fumes and showers.

First thing that mother did that night was “Hair Wash” and she walked to Reay's shop to use their phone and rang matron to tell her were were home safe. Matron told mother to be sure and take me to the doctor regarding my throat, which she did and was told to take me to the Fleming Hospital in Newcastle to have my tonsils seen to. I did go but as there was always a long waiting list I still have them.

UPSTAIRS DOWNSTAIRS MAIDS

After coming out of hospital I had some time at home as Doctor said to give me a few weeks to get well as it was winter. Then we heard of someone at Whickham who wanted a young person to help in the house. The husband had a good job but they had 4 children and could not manage the housework and family, so Mam and I went and were interviewed and it was 'fixed'. I could start on the Monday at 4/6 per week. It did not sound a lot of money but wages were not big in those days, and as mother was a widow with 6 in family, every mouth less to feed was a help.

The next Sunday I was allowed home after lunch and the mistress said she would give me my weeks wages, of course she knew I would return as my "bass" bag and clothes were left. I walked home so I could give mother the whole four shillings and six pence. It was a fair walk down from Whickham to Swalwell, through the gardens, across the "Hiky Bridge" to the turnpike, along to Scotswood Bridge under the buttress then along the tow path to the Wood Houses, then turn and up the street home.

After something to eat I sat down and went to sleep, and was only awakened when it was time for me to go back to work as I had to be back by 10pm. Mam said to brother John, “John, you see her to Blaydon and she can catch the bus to Swalwell”, and then I had to walk to Whickham as there were no buses, so John walked me to Blaydon as whatever mother said went, and I was able to get back in time. Next Sunday the mistress said “I will give you your money tomorrow as it should be” and not knowing any other I agreed and off I went. Tired again I did not get a chance to sleep as Mam began to question me, then let me sleep for a short time before wakening me and said “Come on I am going to walk you back and you can be a little earlier tonight”. As I said whatever mother said you did it.

She talked most of the way but I knew there was trouble somewhere as she had on her dour face that we all knew and when we got there to my surprise she followed me in and said “I have brought my daughter back Mrs ---- to collect her things as she is not staying to work here”. My mistress replied "Oh and why?". Then Mam let loose. I had been hired as a helper in housework but no mention had been made of washing and ironing or being a night nurse to two children which meant I got next to no sleep. I had been told I would have a room to myself but it turned out I would not only look after the two children but also share their bed. She ended up by saying “Go get your things and we will be gone after Mrs ----- has paid you your wages”. By this time Mr ----- was there and he offered to pay more money but Mam said “No you will not or not to my daughter, it is almost like slave labour 6am to 10pm.” They had said I would be finished at 6pm and as I would be living there I would have each night off, and I could go out on a night time. I never got one night off not even to sit down as "She" needed to rest so I had 4 kiddies after tea to bath, feed baby and put them all to bed, dishes to wash etc. Mr ----- never got home before 8 to 8:30pm so it seems he never realised what was happening. Anyway I got my 4/6 pence and I remember Mr ----- asking Mam how we would get home and was told we would walk and we did. That was twice that night that mother had walked that distance but being hard done by she would stick up for you. When I went to get my "bass" bag and my clothes she said to Mrs ----- “You had better go with her and then you can not turn around and say later that we have anything of yours. We may be poor but we are honest”.

On the way home I got “Well that's that, next time you work for anyone it will be for someone that is better than us and not a jumped upstart”.

A few weeks at home and we heard that Mrs Roberts the chemist's wife needed help at home in Bowland Terrace at Blaydon on the bank, there always seemed to be hills wherever I worked. When we went she took us into the drawing room, strange as usually you were interviewed in the kitchen, then after a talk she said “Perhaps you would like to see the work”. A longish kitchen with a range which I could see was for use and not an ornament, outside laundry, dining room, drawing room, hallway and lobby. Upstairs were 3 bedrooms with a large landing and a bathroom, then another big landing used for storage and a large attic used by the son and daughter in bad weather, as a play room. This room had big "dormer" windows and I loved that window as when I was cleaning the room I could look out and see for miles around. We settled at 5/6 pence a week and I would start on the Monday at 8:30 in the mornings except Sundays when it would be 9am, then on weekdays I would finish at 4:30 to 5pm and Saturdays and Sundays at 1pm. I stayed there for two years.

She came from Worcester and her father was retired so their income was much less than they had been used to and her mother was an invalid who was looked after by her other sister who was at home. Once a year at the summer holidays Mrs Roberts and the two children went there and looked after the mother to give her sister a holiday. From what photographs I saw it must have been a large house in its own grounds and orchards as we regularly received boxes of fruit (peaches etc.) from there. Mrs Roberts would stay for 6 weeks and Mr Roberts would get a relief in the chemists shop for a week and go down as well. The first five weeks she was away I would look after him and most days I could be at home at 1pm just leaving a table set with cold meats and salad. He was gone in the mornings when I got there but sometimes we would pass on the road. He was hopeless in the house always having had someone to look after him.

The last week while he was away his two maiden sisters came and stayed. They lived at Monkseaton and having equal shares in the chemists business took "charge" of it in his absence. They were no trouble as they did their own rooms and helped a great deal. Mrs Roberts was a lady in every regard, as when we 'did' a room she worked with me and as I did the carpets and surrounds (carpet squares in the bedrooms), she cleaned the furniture. On washdays she worked with me just the same and also provided hand cream and insisted I use it, as well as in summer she made me wear a hat when I pegged out the washing and in winter a scarf, coat and gloves underneath rubber gloves that she provided.

My wage gradually increased to 8 shillings a week then I decided to find a live in position, although in a way I was sorry to leave as I had learned a lot of things that I could not do at home. We preserved fruit and made jam and I was always given jars to take home, Master Cecil and Miss Dorothy were well mannered, at times mischievous, but never cheeky. The meals were well cooked, she did all the cooking and there was always plenty but never too much.

I went to the Domestic Servant's Registry where you registered and told them what I would like to do and in what district, and sometimes you would get a job straight away. I landed a job at Axwell Park in the home of the Deputy Headmaster of the Approved Boys School. “She” thought she was a lady and I stayed only 7 months. Enough time to save some money as I wanted to start and buy myself some good clothes, as by now I was allowed to keep my own money and up till then I had been giving all my wages to my mother and she gave me a little back.

Mrs ----- (the deputy's wife) used to tell me what to wear and even when to change my stockings. As I only had two morning outfits and one afternoon outfit it was sometimes a problem, especially when you were kept flat out from 6am till sometimes 10-11pm or even 12pm if she had a party. Things finally came to a head, I had had every second Sunday off before lunch, if I gave up a Saturday night, well this week she said that I would have to have Saturday and Sunday nights as I was needed to serve lunch on Sunday as her hairdresser was coming and he would be staying for lunch (she had been going to the shop but to a private sitting). Fair enough, Sunday morning I opened the door and on the steps was Joe Armstrong, “Hello” he said “did not know you were working here but how is your mother?”, Well we talked for a few minutes and then I knocked and showed him to the room and in he went. I served lunch, cleared away and knew there was trouble brewing each time she looked at me. He cut her hair and went away and hardly had he gone down the drive than the bell rang. “How dare you to keep my visitor standing and what business had you to keep Mr Armstrong talking”. Normally I stayed mum but she got my back up so I said “Mr Armstrong was enquiring about my mother”. Well that did it. “You are lying, what possible interest can my friend have in your mother”. I took her breath away when I replied. “Oh they are cousins and my eldest sister worked for him till recently. Why not ask him next time he comes again. Will that be all” and I walked out.

A very uneasy truce existed till his next visit when I met him at the door and showed him into the room in which she was sitting. When she said “That will be all” I said “Oh no I am waiting for you to ask Mr Armstrong about how he came to enquire about my mother”, and when he said they were cousins it really took the wind out of her sails. After lunch and he had gone I went in and said “I am going now and will be back by 10pm as usual and oh I would like to give you a week's notice as from today as I am not a liar”. She tried to get me to stay but I had enough of her but Mr ----- was very well liked and he even brought the dogs to the park gates on a night time to meet me as it was a very lonely walk up to the school with the trees rustling and Jenny Owls hooting, it was scary. The boys in the school did not like his wife for if they passed her outside and did not stop to take off their caps they were reported as insolent. I heard that he was made headmaster a few years later but if she was the “Heads” wife she would make things miserable for all of them.

I had one or two more jobs before I was married but the best one was at Priorsdale on Clayton Road at Jesmond, Newcastle when I was Cook-general and my cousin Annie Bulman was Home-parlourmaid. We had a Gardener-handyman, and Washerwoman who cleaned all the back kitchens as well and I did the cooking, kept my kitchen clean and did the morning room and the hall whilst Annie did all the upstairs and the dining room and waiting on, then we did the drawing room together. The master had retired so their income had dropped considerably but there was still Mr and Mrs Robson, a daughter of about 30 years and a son who lived out. They were very considerate about time off and this arrangement was good as there was always Annie or I left in to work it out between us.

Odd things crop up as a few months ago I was talking to Ena Kelly (and old friend from our village) about working in “Private service” and it came out that she had taken on my job a few months after Annie and I had left and they had employed a “Temporary”. The house was beautiful as a home but was later a Youth Community Centre. We had, I remember, a lady school teacher as a boarder whose board money helped out the household.

My wages at Priorsdale was 12 shillings and 6 pence a week and you found your own uniforms. Only wealthy people bought servants uniforms in those days.

I forgot to mention about the arrangements at the Registry, when a mistress applied for a maid she paid a fee but the "maid" did not till they were found a job when they paid a commission out of their first week or months wages according to the arrangements. When you went for an interview it was the rule that the mistress gave you your bus or car fare even if you did not get “fixed up”. If you were not suitable and she was a generous person they would often give you a bit extra for the trouble they had put you to.

Photos below - Ready for work as housemaids. Left - Hannah Liddle, eldest sister of Edith Robson.

Right - Mary Elizabeth Liddle Jnr, second youngest sister to Edith Robson.

MORE ODD CUSTOMS

Years ago in England we had some odd customs or at least to this modern generation it would seem that way. For instance almost every place, no matter how small or scattered, had some woman who was always ready to come in case of sickness. Often before the doctor could be brought she would bring a baby into the world, poulticed someone with pleurisy or pneumonia (no antibiotics then) or set a broken leg, in fact anything needed. No formal training just long experience and a natural sympathy with sick people.

We had one who lived on the other side of the street and known to all of us young'uns as Granny Chapman, she was short, plump and with silver hair. Always when she came she wore a black blouse and a long black skirt with a snow white apron.

My father one Saturday said he did not feel well enough to go to the pub for his pint and went to bed. When he was not any better on the Sunday my mother sent me to get Granny and as soon as she arrived she said “We will need to poultice”. By night time there was no change and someone went for the doctor. Dad died on the Monday.

Granny Chapman and her daughter did everything custom said must be done. The walls where the “bier” was to stand was draped with white sheets, pinch pleated and tacked to the wall (the bier is the stand for the coffin). Each pleat was fastened with a bow of black ribbon and the beir was draped the same. When the undertaker came with the coffin, Granny and Lizzie sent everyone out of the room till they were finished. Granny had sent my uncle to the undertakees and he had arrived first thing on Tuesday morning and returned later that night. Granny stayed with my mother till all the arrangements were made.

On the day of the funeral two women walked in front of the hearse in front of two men. The women would be carrying two wreaths which had been sent to the home. Usually the day before the funeral two neighbours knocked on every door in the street asking for donations toward the wreaths. They were often only two shillings and sixpence each in those days and any money left over was put in an envelope and handed in along with the wreaths with the words "It might help".

If it was a woman who had died two men would walk in front then two women. When it was a child no hearse was needed as the coffin was carried by four teenagers with two following as reserves. The woman wore white gloves and white tulle scarves tied in bows at the front and all the men wore black armbands.

When I was very little the undertaker walked in front of everyone. He wore black, tailed coat and a high hat with a crepe band on it. The hearse was something to behold, all black with silver fittings and mirrors set in the panels. You only see them in museums now. The horses were black, with black plumes on their heads.

Morning coaches were box shaped with black curtains at the windows which were supposed to be kept closed but talk about dark. I travelled in one when a friend of mine was buried and the husband provided coaches, as the cemetery was 8 miles away. All the men walked, including the husband but on the return I gave my seat up to and old man and walked the distance back to the home. This was at Ryhope near Sunderland.

At our cemetery in Blaydon there was a small chapel where the coffin could be taken in and the service held but most folks opted for a graveside service. On leaving the cemetery folks were invited by two women, who stood at the gates, to return to the home of the deceased for a cup of tea and a bite to eat. As a lot of people used to travel some distance to attend a funeral, a spread was usually provided.

Funerals gave relatives a chance to catch up with all the news, who's being married, who's moving where, in fact kept you up to date with the news. People did not do a lot of travelling in those days so they took the chance to see what folks they could.

When my father was buried and before the coffin was put in the hearse, four kitchen chairs were put outside in the street and the coffin was laid on them so that people who for one reason or another could not get to the cemetery, they could take part in a short service usually held by the Salvation Army or the Methodists. As a rule widows did not go to the cemetery, but went about two days afterwards with a friend for company. Most people managed to wear black unlike today when all colours are worn.

It was an unwritten rule also that the coffin had to be taken past the church if at all possible. The under bearers, usually relatives of friends, were all given, unless they refused, a glass of whisky. The women who washed and dressed the deceased were also given a “glass”. I know because a friend and I stayed with one of our friends, and after we had done everything that had to be done when Barbara --- died and before we left to go home, Barbara's mother insisted that we have a glass of rum.

We managed home OK but it was winter and snow had fallen heavily so that coming from a warm house into the cold, then into a warm house, I am afraid all I can remember is walking?... into our lounge room and seeing my husband and eldest son who had been waiting up for me. I sat down on the settee and knew nothing more till the morning but I must say next time I went, I settled for a cup of tea.

Seems funny but carrying out these customs somehow took the edge of the sorrow as my grandfather said once “You live no longer and die no sooner so why not face it”.

Most people, when a baby was born, had within a week taken out a life insurance policy for about a penny a week. I believe this paid out at death about 10 pounds and then you found that when the child was about 10 that they increased it to 2 pence a week, which most people paid for life and which sometimes included yearly bonuses. Preparation for the future they called it.

Photo below - The horse drawn hearse, a legacy of the Victorian era.

SNOW AND SCHOOL DAYS

Australia May 1980 and it's raining again. I don't mind the rain but when we get the heat afterwards well I wilt. Maybe because I came from the North East of England and we had cold winters but of course it also brought a certain amount of fun with it with the snow.